Successful businesses in the competitive age of consumerism relied on creative marketing to give their shops prominence in the public eye and secure new business. Promotional techniques such as discounts and special offers, sales and weekly novelties were deployed in conjunction with focused consumer marketing. Advertisements, trade cards, traveling sales were all weapons in a trader’s arsenal.

Tradesmen made full use of the nation’s many newspapers to promote their establishments. Shops targeted the nobility and gentry in papers like Britain’s first daily newspaper, The Daily Courant as well as provincial papers like The York Chronicle and Weekly Advertiser. Boasting of the range and quality of stock available, regional papers listed ‘highly superior’ goods newly arrived from London, and highlighted local retailers’ connections with royal patrons.

Like other current interest areas such as politics, newspapers provided businesses a platform for competitiveness to descend into open warfare. Shopkeepers engaged their rivals in lengthy and sometimes bitter printed battles of words. In 1783 the pages of the York Courant became an advertising battleground as rival merchants, William Tuke and John Wormald vigorously disputed each other’s claims about the quality of their respective supplies of salt.

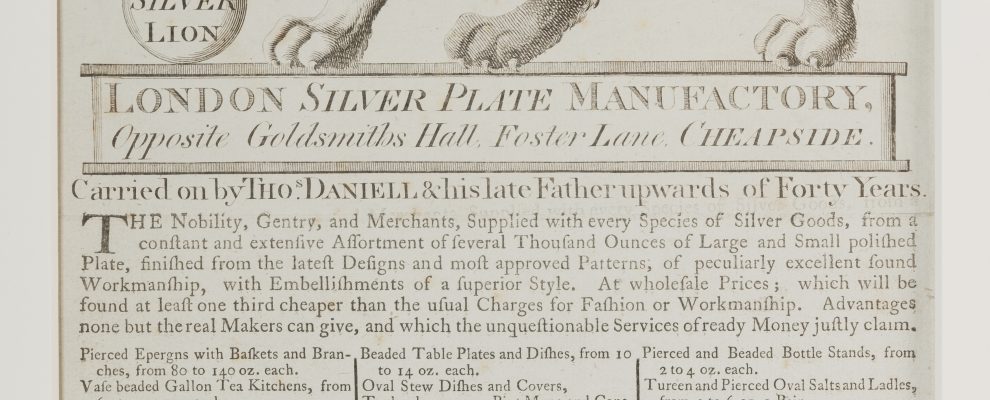

Beautifully engraved trade cards were another particularly effective promotional tool for merchants. Carefully considered aesthetic qualities like elegant design motifs attracted notice. Limited print-runs, lavish treatment, and cost of production subtly signalled the exclusivity and superiority of a shop. In addition to advertisement, they acted as invoices, sent to buyers after a purchase, which encouraged return custom. This customer–retailer relationship was reinforced further as shoppers kept trade cards as souvenirs of their experiences. Historians Helen Clifford and Maxine Berg also note that trade cards were sometimes sold alongside other prints, making them attractive to collectors and antiquarians alike. Their attraction as collectors’ items has remained in part due to their quality and designs.

Eighteenth-century efforts to gain business were not limited to print media. In order to further their commercial reach some manufacturers employed commercial travellers called ‘riders’. Similar to travelling salesmen, these commercial travellers carried hand-annotated catalogues and price lists, along with ‘half-samples’ to show prospective customers. This method allowed manufacturers to sell to multiple levels of customers from wholesalers, to retail dealers and even directly to the public.

Many retailers used a similar method to reach audiences beyond those that visited the shop itself. Capitalising on the versatility of their products, drapers often sent fabric samples for perusal to the homes of their wealthiest clients. Swatch books were also employed, providing a condensed summary of the range of items for sale. To entice customers further, these were accompanied by personal recommendations and ‘special’ deals. Stationer and publisher Rudolph Ackermann built upon this, allowing drapers to disseminate samples of their fabrics in his popular monthly publication ‘The Repository of Arts’. Including samples in a publication already arriving in the home was a particularly sophisticated approach and remarkably akin to modern marketing practises.

From mass marketing newspaper advertisements to hand-delivered samples, Georgian tradesmen employed many methods to build a large customer base. Platforms like newspapers enabled healthy (and sometimes aggressive) competition that allowed customers to feel informed when making their purchases. Once a choice was made, tools like trade cards and special offers strengthened customer–supplier bonds to ensure continued business, all contributing to the survival of the consumerism that defined Georgian life.

Further reading:

Maxine Berg, Luxury and Pleasure in Eighteenth-Century Britain, Oxford University Press, 2007.

Maxine Berg and Helen Clifford, ‘Selling consumption in the eighteenth century’, Cultural and Social History, 4:2, 2007.

Fairfax House, Made in York, 2017. (link to online shop?)

Links to collections:

The Fitzwilliam Museum www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/gallery/tradebills/home/tradecards.html

Waddesden Collection of trade cards – a searchable database of mostly European eighteenth century trade cards. https://waddesdon.org.uk/the-collection/explore-the-collection/

Bodleian Library – the John Johnson Collection of Printed Ephemera. The searchable database includes an array of eighteenth-century trade cards and bill headings. www.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/johnson/online-exhibitions/a-nation-of-shopkeepers

Sarah Shields Ed and Aimee Keithan Ed

Name: Rachel Wallis

Title: Assistant Curator & Registrar

Source: Consuming Passions: Shopping for Luxury in Georgian Britain (Fairfax House, 2015)