Animal baiting and organised blood sports such as cockfighting and bull baiting were highly popular entertainments in the eighteenth century. Often held to coincide with horse racing events to help maximise the number of attendees, they provided ample opportunities for gambling and drinking. Such events were mostly attended by men and attracted spectators from across society, the visceral pleasures of the fight and the opportunities to bet proving to be appealing regardless of social rank.

Many provincial towns had purpose-built bull-rings. Baitings (which on occasion featured badgers and bears as well as bulls) often took place in busy market places or town squares. In York bull baitings had been held regularly since Elizabethan times, and took place next to the Butcher’s Market in St Sampson’s Square. Bulls would be tied to a tether and attacked by dogs. It was believed that meat from a bull which had been baited had a superior flavour, and bull baiting, as a legal requirement prior to slaughter, remained on the Statue Book throughout the eighteenth century, although the law was only periodically enforced.

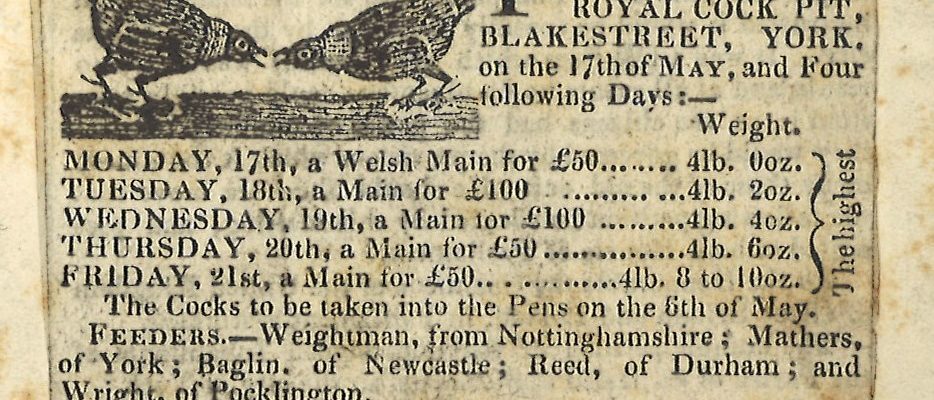

In addition to the gruesome spectacle of animal baiting, cockfighting is known to have been popular in eighteenth-century York. There were three purpose-built cockpits in the city: the ‘Sign of the Cock’ at Aldwark, ‘Warton’s Pit’ outside Bootham Bar, and ‘New Pit’ in Coffee Yard. Cockfights were often organised by respectable gentleman, such as Sir John Lister Kaye, M.P. for York in the 1730s, and were widely advertised in advance. The first day involved weighing and matching the birds as closely as possible. The next two to six days (depending on the length of the tournament) were spent in battle. A fight could last up to three hours during which time spectators made frantic bets. The winner was the last bird standing. To increase the chances of victory and ensure the most spectacular injuries, cocks had their beaks sharpened and their neck feathers clipped, and wore metal spurs called gaffles. Types of matches included the ‘Welsh Main’ which was a knockout contest between sixteen birds which fought until there was only one bird remaining alive, and the ‘Battle Royal’ in which any number of cocks were pitted against each other at one time, the winner again being the last bird alive. Even more brutal was the sport of ‘Cock Throwing’, where coksteles, which were special weighted sticks, were thrown at a tethered bird until it died. To make the game last longer, people would sometimes support the bird’s legs with sticks, or place them in a ceramic jar to stop the bird moving around.

Whilst sports such as cockfighting and bull baiting proved to be hugely popular and profitable, many contemporaries considered them to be barbaric forms of entertainment. Daniel Defoe recorded his objections to cockfighting in 1724, noting that whilst he admired the courage of the birds, he considered the sport ‘to be a remnant of the barbarous customs of this Island, too cruel for my entertainment’. A contributor to the Edinburgh Weekly Magazine in 1783 similarly declared it to be a ‘disgrace to human nature’ and questioned what type of person ‘can with pleasure behold two useful and beautiful animals tearing one another, bleeding and expiring in pain’. Cockfighting and animal baiting were finally outlawed as forms of entertainment by the Cruelty to Animals Act in 1835.

Source: In Pursuit of Pleasure: Entertaining Georgian Polite Society (Fairfax House, 2016)